HIV/AIDS PREVENTION: Interventions in the Pipeline or in Trial

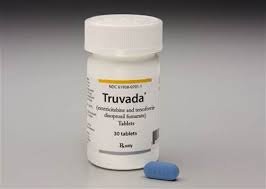

HIV/AIDS PREVENTION: Interventions in the Pipeline or in Trial The following interventions are currently being developed or evaluated: • Microbicides. Most microbicide products are currently in preclinical development; however, 18 products are being evaluated in clinical research studies, most in small phase 1 safety and acceptability trials. Three phase 3 effectiveness trials are currently under way. • Diaphragms. The safety and effectiveness of the diaphragm and Replens gel in preventing HIV and STIs among women are being tested in an ongoing phase 3 randomized controlled trial in South Africa and Zimbabwe. Two trials, in the Dominican Republic and Madagascar, are planned to test the diaphragm’s effectiveness against bacterial STIs. Several other trials in Sub-Saharan Africa are planned to test the acceptability and safety of the diaphragms plus microbicides. • Circumcision. Two randomized controlled trials are under way in Kenya and Uganda to examine whether circumcision confers protection among adult men. • Community-based VCT. Project Accept is a communitybased VCT trial in 32 communities in South Africa, Tanzania, and Zimbabwe and 14 communities in Thailand.Communities are randomized to receive either a community-based VCT intervention or a standard clinic-basedVCT. The community-basedVCT intervention has three major strategies: to makeVCT more available in community settings, to engage the community through outreach, and to provide posttest support. • HSV-2 treatment. One study in six countries will determine the efficacy of twice-daily acyclovir in reducing susceptibility to HIV infection among high-risk, HIVnegative, HSV-2 seropositive women and men who have sex with men. A companion study will also be conducted to assess whether acyclovir reduces HIV infectiousness in individuals infected with both HSV-2 and HIV. • Tenofovir for preexposure use. Studies are now enrolling participants at three West African sites and will soon begin in Botswana, Malawi, Thailand, and the United States. • Antiretroviral therapy to prevent sexual transmission. A phase 3, randomized, controlled, multisite trial to assess whether antiretroviral therapy can prevent sexual transmission of HIV in serodiscordant couples will begin in Brazil, India, Malawi, Thailand, and Zimbabwe. • Vaccines. Although preliminary results from a phase 3 clinical trial in Thailand found that AIDSVAX failed to protect against infection, several other vaccines are being developed. Merck and GlaxoSmithKline have unveiled sizable vaccine programs and moved products into human testing. An International AIDS Vaccine Initiative U.K.-Kenya team is in the midst of intermediate human trials of DNA/MVA (modified vaccinia virus Ankara), and Aventis Pasteur is taking ALVACAIDSVAX into the final phase of trials. The South African AIDS Vaccine Initiative is preparing for the country’s first trials, India’s prime minister has pledged national resources for vaccines, and the European Union is broadening its vaccine research for HIV. • Behavior change programs for people with HIV. In recent years, a growing number of public health experts have proposed implementing prevention interventions that target people with HIV (De Cock,Marum, and Mbori- Ngacha 2003; Janssen and others 2001), although evidence on the most effective strategies to encourage safer behavior among people with HIV is lacking. RESEARCH AGENDA As in many other areas of public health in developing countries, a profound tension exists between (a) the need for research to discover new technologies and interventions for both prevention and care and (b) the need for research to learn how to effectively apply the technologies that are currently available. The most important barrier to control is lack of knowledge about how best to implement packages of existing interventions at the appropriate scale to maximize the effect of prevention and care interventions and to protect the human rights of those affected by the epidemic. Accurate surveillance data are needed on risk behaviors, and effectiveness research is needed to discern what interventions work where and how they do so. Unfortunately, few rigorous evaluations of new or existing interventions have been conducted using large prospective cohorts, with the result that, for many interventions, convincing data on effectiveness are not available. Finally, research on policy or structural interventions, which by definition must be conducted on a population level, is also insufficient. These interventions include the development and testing of such policy tools as changing the tax structure, regulating the sex industry, and guaranteeing property rights and access to credit for women. Box 18.7 lists new prevention interventions in the pipeline. Although numerous promising interventions are listed, results for most of these strategies are at best years away. Centuries hence, when future generations study the history of our time and the epidemic that killed 50 million or perhaps many more, the most difficult question to answer may well be “why did they invest so little for so long in developing a vaccine?” Creating such knowledge is about as close as one can get to a pure international public good, and the lack of global cooperation in adequately funding such research is an indictment of global commitment to multilateral cooperation. However, given both the uncertainty about whether developing an effective vaccine is possible and the long delay until a new vaccine can be widely applied, vaccine development efforts must be accompanied by the development of other new biomedical and behavioral prevention technologies. In contrast, research on care and treatment has been far more successful than research on prevention, and innovation in new therapies continues apace. The ability of HIV to rapidly evolve resistance to antiretroviral drugs, combined with the existence of an important market in high- and middle-income countries, appears to ensure continued investment in new drug development. In addition, because treatment generally has important commercial returns, HIV therapies, unlike behavioral interventions, have benefited the most from private sector investment. The paradox is that research on the behavioral aspects of adherence to drug regimens would improve the effectiveness of antiretroviral therapy, and thereby benefit both commercial and public interests. The greatest research challenges in relation to care and treatment in developing countries do not revolve around new drug development. They revolve around how to adapt care and treatment strategies to low-income, low-technology, low– human resource capacity settings in ways that maximize adherence; minimize toxicity, monitoring, and costs; and maximize the prolongation of high-quality life from antiretroviral therapy—all without damaging existing and often fragile health care infrastructure that must also address other health concerns. Although simplified regimens, such as delivering multiple drugs in a single tablet and fewer doses per day, are desirable everywhere, they are especially important in lowresource settings. Similarly, low-technology, low-cost monitoring tests for antiretroviral therapy toxicity and for immunological and virological responses to treatment are especially needed in low-income countries, which otherwise must centralize testing—an especially difficult prospect when transport and communications systems are poorly developed. CONCLUSION Despite the glaring deficits in AIDS research, the magnitude and seriousness of the global pandemic calls for action in the absence of definitive data. The appropriate mix and distribution of prevention and treatment interventions depends on the stage of the epidemic in a given country and the context in which it occurs. In the absence of firm data to guide program objectives, national strategies may not accurately reflect the priorities dictated by the particular epidemic profile, resulting in highly inefficient investments in HIV/AIDS prevention and care. This waste undoubtedly exacerbates funding shortfalls and results in unnecessary HIV infections and premature deaths. The lack of good data—and thus the ability to tailor responses to epidemics—may be somewhat understandable when the burden of disease is minimal and the resources dedicated to it are similarly small. Neither is the case for HIV/AIDS.

Comments

Post a Comment